By Jason Weeby, Director of Strategic Initiatives, NewSchools Venture Fund

Occasionally, after the kids are in bed, my neighbor comes over to have a beer. Sitting six feet apart in my backyard, we compare notes on how we’re coping as we raise young kids during a pandemic and a national reckoning with racism. After the delight of discussing the new baseball season, our most recent conversation turned to our school district’s reopening plan (distance learning for now) and eventually to a new phenomenon: pandemic pods.

The perspectives on pandemic pods — sometimes called learning pods — are as varied as those on schools in general. Clara Totenberg Green’s opinion piece in the New York Times sounding the inequity alarm has received a lot of attention. Conservative pundit, Andy Smarick sees the trend as an example of bootstrapping that’s uniquely American. School choice advocate Chris Stewart sees the podding as another form of choice that should be available to everyone regardless of socioeconomic status. Even Randi Weingarten, the head of the nation’s second-largest teachers union has weighed in saying, “The pod and small group learning ideas are good ideas, but we have to ensure that they’re actually equitable.” Although pandemic pods are new, issues of race, class, opportunity, and equity surrounding them are not.

So what are pandemic pods, and what might they mean for students, families, and our education system?

What is a pandemic pod?

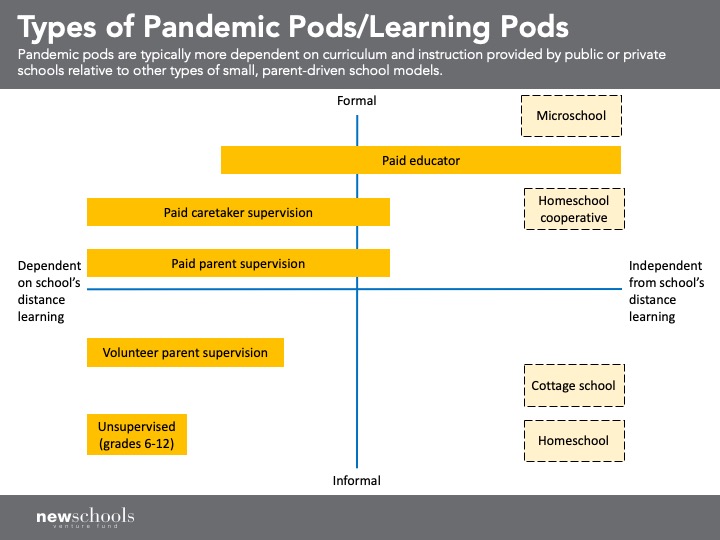

Pandemic pods are small groups of students that learn together while schools are closed. Parent-driven, self-organized schooling isn’t a new idea. Pandemic pods share a lot in common with other schooling models that prioritize small groups such as homeschooling, homeschool co-ops, cottage schools, microschools, and Freedom Schools of the Civil Rights Era. In these school models, parents proactively opt out of the traditional school system and take more direct control over their children’s education for a wide variety of reasons such as religious beliefs and institutionalized racism.

Unlike the examples above, pandemic pods are cropping up because of school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. What they look like ranges from two or more families supporting students using curricula and instruction provided by their school to fully independent microschools that employ teachers and create curricula.

Some parents are forming pods now, hoping to find like-minded families, hiring free agent teachers, and lobbying principals to have podded children in the same class. Much of the matchmaking is happening on Facebook or other online platforms. Others are waiting to see who’s in their kids’ classes and what the distance learning from their local schools will look like.

What might pandemic pods mean for education?

The evident and likely downside to pandemic pods is that they will exacerbate already troublesome opportunity gaps between wealthy and white students and low-income students and students of color. When low-income students and students of color are at a disadvantage with distance learning, more affluent families are in a position to supplement — or completely replace — what their public schools can provide. Parents that work from home and can afford to hire someone to support their children’s learning have access to technology, the internet, and a panoply of online platforms, apps, and materials that will be able to keep their children’s education progressing. Those who are essential workers, have a primary language that’s not English, and can’t afford devices and wifi run the risk of having their children’s learning stall. For essential workers with young children, the pandemic pits the need for childcare directly against the ability to maintain a job.

If that weren’t enough, pods could increase racial and socioeconomic segregation even beyond what we see in schools. Families that pod up are most likely to look a lot alike in terms of race and income because most schools and communities are demographically homogeneous. Even in diverse communities, families are likely to have homogeneous social networks that will result in pods without much difference.

One typical response to this is to diversify pods by forming family groups that include students of different races and income levels. It’s feasible that this could be done in some neutral way where parents of different races and socioeconomic statuses come together to form a pod. Still, since pods are a trend initiated by those with means, diversification would come at their behest. At best, diverse pods created with good intentions and deliberation would create bonds and minimize otherness between families and students who wouldn’t otherwise spend significant time together. At worst, wealthy families inviting poorer families to their pod are noblesse oblige and assuaging white guilt. As R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy wrote, “If good-willed pod families don’t interrogate why segregation happens in their life, their ability to incorporate difference is already troubled.” I like to think that diverse pods could be an inroad to diverse schools, but racial integration driven by white parents doesn’t have a strong track record in public education.

Another response is to support low-income families to establish pods so they can reap the same benefits in terms of socialization, support, and work hour supervision for their kids. And while much of the pod conversation centers on the privilege and agency of white and wealthy parents starting pods, they don’t have a monopoly on them. There’s a long history of Black families homeschooling and creating small, self-organized schools to protect their children from racism and stereotyping.

Seeing the demand for pandemic pods growing (and desperate customers with money), many nonprofits and schools have reoriented themselves to provide services that help families set them up. Three independent schools — The Portfolio School, Hudson Lab School, and Red Bridge School — have set up Learning Pods, a service that helps families form pods and then provides ongoing support. Swing Education, an organization that matches substitute teachers to schools, has created a service called Bubbles that provides background-checked teachers for pods. All of these services come with fees that are out of reach for many families. If there are similar free services, I haven’t seen them yet. But creative public and civil sector solutions are emerging.

For instance, San Francisco Mayor London Breed recently announced an initiative to set up learning hubs around the city to provide space and supervision for students with distance learning barriers. If successful, the effort will remove some obstacles for low-income students to be part of small, in-person learning environments. With everything school districts are managing to reopen in a few weeks, it’s hard to imagine them also creating an infrastructure to help lower-income parents create pods. However, individual schools might be able to pull it off over the coming months as they settle into their new models. Local governments and community-based organizations could step into the breach to facilitate pod-formation as an attempt to level the playing field. Juliet Squire and Alex Spurrier at Bellwether Education Partners propose several methods for making pandemic pods more equitable including expanding the pool of teachers and providing high-quality materials and support to parents.

For all the attention pandemic pods are receiving, the long-term effects on the U.S. education system aren’t likely to be significant relative to more enduring and further-reaching issues like de facto school segregation and funding disparities. For there to be a credible competitive threat to school districts themselves, there would have to be a perfect storm of widespread demand for Education Savings Accounts and supply of quality education service providers. We’re likely to have a vaccine before that all comes together. However, families exposed to new ways of schooling and empowered by their independence from traditional structures may opt to evolve their pod into a microschool or charter school in what could be a wave of grassroots innovation. But most likely, parents that form pods will be relieved when they can send their children back to school and return to a sense of normalcy. I know I will.

My neighbor and I didn’t come to any conclusions about what pods might mean for our neighborhood elementary school or our second-grade boys who go there. Still, we’re keeping the door open to the idea of podding up (after we know our classroom assignments) while being vigilant about what our actions might mean for others.