Across the country, educators, policymakers, and innovators are urgently working to help schools recover from the academic and mental health impacts of Covid-19 and pandemic-related school closures. As they make the necessary investments and develop programs to accelerate student progress, it’s imperative to make decisions based on what works.

Our national portfolio of innovative schools and our Expanded Definition of Student Success (EDSS) longitudinal dataset provide a robust set of insights about effective innovations and practices. We believe these insights point to critical actions educators should take to build the post-Covid future.

Our EDSS framework focuses on three key components of student development: a strong academic foundation; positive school culture and climate; and social-emotional mindsets, habits, and skills that help young people pursue their most ambitious dreams and plans.

We leverage this framework to advance both excellence and equity across our national portfolio of 110 innovative public schools. These schools will serve more than 82,000 students at full enrollment, and educate a higher proportion of Black, Latino, low-income students and students with disabilities than the national average.

Since Fall 2016, we have surveyed students every semester to understand and improve their schooling experience. Because our EDSS dataset spans multiple years, it represents an incredibly rich source of information about student performance and wellbeing from before, during, and after Covid-related school closures.

Looking across our portfolio of schools, we find evidence of resilience and recovery tied to a commitment to positive school culture and social-emotional learning. Indeed our data suggests that with early and targeted interventions to support social-emotional learning, it is possible to interrupt and recover from Covid-era academic backsliding.

Alongside our EDSS evaluation partners at Education Analytics, we generated four specific insights that educators can use to map out multiple routes to recovery. We will share more specific stories of the actions school leaders have taken to achieve these results in future publications.

Insight 1: School culture improved and students demonstrated new depths of social emotional skills at the height of the pandemic

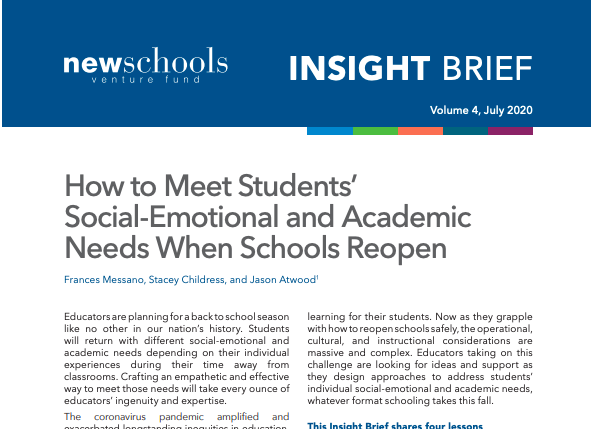

When we examined indicators measuring the health of school culture — such as school safety, teacher-student relationships, classroom engagement, perceptions of fairness, and rigorous expectations — we found that students reported statistically significant improvements when schools reopened in the 2020-21 school year than before the pandemic. To illustrate with one powerful example, between Spring 2017 and Spring 2021, we see a 15-point increase in the way 8th graders assess the strength of their relationships with teachers. It is emblematic of an overall trend we see in nearly every grade level.

These numbers challenge the dominant narrative that Covid-era schooling resulted only in losses for students. Our data show that the Herculean efforts teachers undertook to make their students feel safe, welcome, and nurtured made a real difference in their students’ lives.

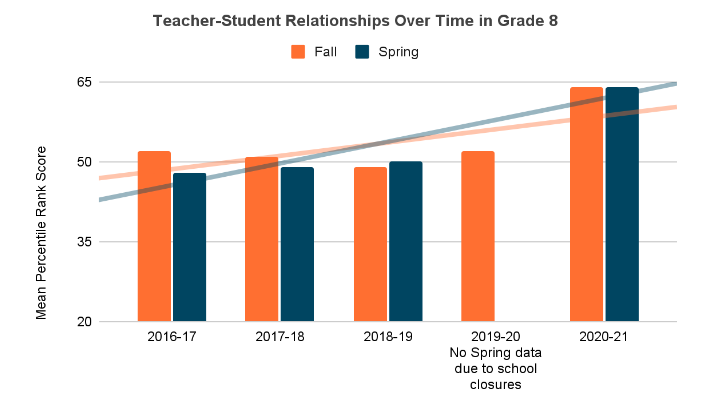

In the social-emotional domain, students reported statistically significant higher ratings on their levels of self-management, self- and social-awareness, and learning strategies in 2020-21 relative to pre-pandemic baselines in 2018-19 across multiple grades. See, for example, the consistently higher self-management scores among students in Fall 2020 compared to Fall 2018.

In our view, these results demonstrate the distinctive mindsets, habits, and skills that students drew on to navigate the uncertainty and crisis they faced during the pandemic.

Insight 2. Students with strong social emotional skills and favorable perceptions of school culture before Covid performed better academically when school reopened

We found that over an 18-month period from Fall 2019 to Spring 2021, student impressions of school culture and their self-ratings on social-emotional learning were positively correlated with math and reading outcomes, as measured by NWEA’s MAP Growth assessments.

In other words, students who had highly favorable impressions of their school’s culture and/or strong perceptions of their social-emotional skills before the beginning of the pandemic subsequently went on to achieve higher scores in math and reading when schools reopened. This is a clear demonstration of the long-term influence of environmental conditions and social-emotional learning as a support for academic success.

It also emphasizes the importance of longitudinal studies focused on multiple dimensions of positive youth development. Because our schools survey students year-over-year, we can illuminate the compounding effect of an expanded definition of student success, especially since some school culture and social-emotional factors need a longer time frame to bear fruit.

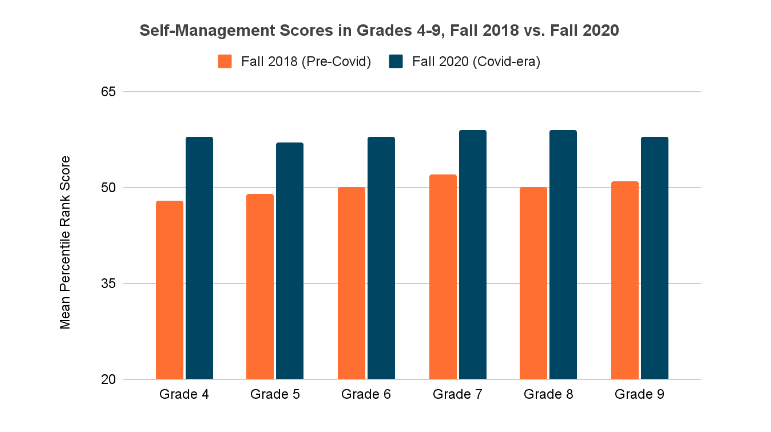

Insight 3. Strong social-emotional learning protected middle school girls from Covid-era learning losses

Our EDSS dataset is rich enough to explore the educational experience of specific student subgroups and the interaction between different variables such as gender, grade level, and school subject.

This led to an important discovery about the relationship between social-emotional learning and progress in math for middle school girls during the pandemic. We found that girls in grades 6-8 with high SEL skills pre-Covid exceeded typical growth trajectories in math that were established before the pandemic. More simply: They did not experience learning loss. In fact, this group of students demonstrated nearly three-times the amount of math growth in 18 months as their female peers who reported low SEL skills pre-pandemic.

This finding gives us another convincing data point that Covid-era learning loss is neither inevitable nor insurmountable. Early and targeted social-emotional interventions can provide a foundation for later academic success.

Insight 4. Students were more likely to meet their growth goals in math and reading when they had strong positive perceptions of school culture

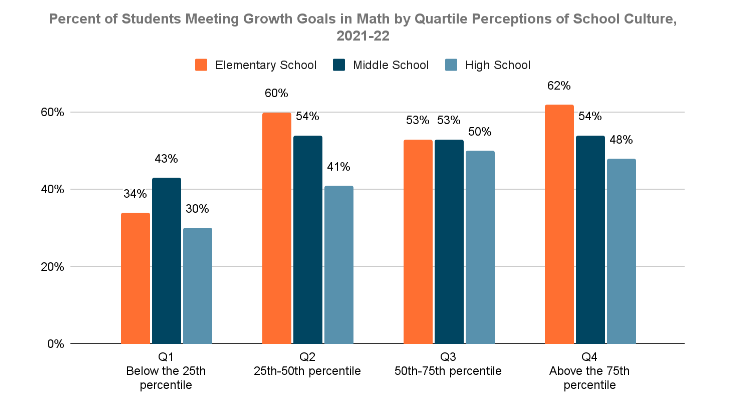

When we probed the relationship between student performance in academics and their perception of school culture, we found a strong relationship. For example, in 2021-22, elementary school students who had the most favorable impressions of school culture were nearly two times more likely (62% vs. 34%) to meet their growth goals in math. The inverse held as well. If students were in the bottom quartile of school culture ratings, they were more likely to miss their growth goals in math.

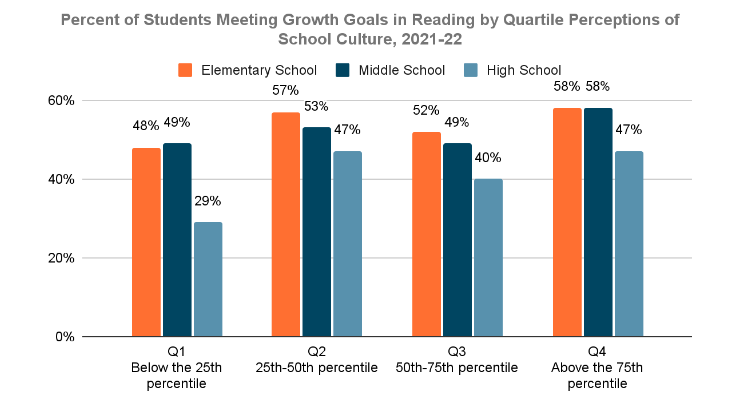

A similar—though not as dramatic—trend played out when we looked at the quartile distribution of school culture ratings and the likelihood of meeting growth goals in reading. The number of elementary, middle, and high school students surpassing their growth targets tended to increase as students exhibited more favorable impression of school culture.

These findings shed light on the importance of factors like rigorous expectations, teacher-student relationships, and student engagement. They suggest there is a baseline positive perception of school culture that students need to perform well in school. Our analyses point to the critical importance of getting beyond the 25th percentile threshold to support the academic performance of students, especially at the elementary and middle school levels for math. For high school students and reading, the threshold is higher, reaching the 50th percentile of positive impressions of school culture to improve the likelihood of meeting growth goals.

We also compared the amount of academic growth of students who scored the lowest (i.e., below the 25th percentile) or highest (i.e., above the 75th percentile) on each construct of our EDSS framework from Fall 2021 to Spring 2022.

This allowed us to learn that among elementary school students, sense of belonging was the most consequential variable on differences in math outcomes. Students with the strongest sense of belonging had significantly more growth in math than their peers who felt the least connected to school. This difference is the estimated benefit of attending school for an additional 4.7 months on top of a typical 180-day school year. Differences in perceptions of school safety had the largest practical impact on reading scores at the elementary level: Students who felt the safest demonstrated reading growth that is equivalent to 4 additional months of instruction.

In the middle school years (i.e., grades 6-8), students with the highest relative scores on sense of belonging, rigorous expectations, and the social-emotional competency of growth mindset had statistically significant more math growth. These differences are estimated to add 1.5 to 2 months of learning to their schooling experience.

At the high school level, when students felt exceptionally safe in their school, their reading trajectories were boosted as if they had received 4.5 months of additional instruction relative to their peers who felt the least safe in school.

These results speak to the importance of looking at student survey results by grade bands and paying special attention to those at the lowest end of select measures.

***

The pandemic dealt a serious blow to student academic progress. It laid bare and heightened long-standing inequities in our schools. Given the magnitude of these challenges, charting a viable path forward can seem like an overwhelming task.

Yet when we consider the experience of students across our schools, the reflections of our school leaders, and the insights generated through our EDSS dataset, we see ample reasons to be optimistic. Across our portfolio of innovative schools, we’ve identified promising practices that educators have implemented during the pandemic that are worth keeping for good. We will share more of these practices in future blog posts.

This is the value of embracing measures of progress beyond test scores alone. By understanding student perceptions of their school climate and culture, how they are building social-emotional learning skills, and integrating these experiences with measures of academic growth, we can identify strategies that help young people thrive.

As portfolio member Margie Lopez Wait, Head of School at Las Américas ASPIRA Academy in Newark, Delaware shared: “Our impact and success is in the hearts and minds of our students. It is seen in their smiles, felt in their hugs, and realized in their confidence. This is the data that means the most.”

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://www.newschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/GFE_Conference-Draft-10-18.mp4?_=1