The number of schools designed for personalized learning is growing rapidly. At NewSchools, we’re helping teams of educators launch many such schools through our Catapult program.

Why did we decide to focus here? One reason is early evidence of the positive effects personalized learning has on students. What do we know so far? The RAND Corporation recently released the findings of the third year of a study of schools implementing personalized learning.[1] The quasi-experimental study follows 11,000 students in 62 schools for two years and includes additional analysis on a subset of 21 of the schools that have three years of data. Among the 11,000 students, 75% are Black or Latino and 80% are low-income. It’s the largest and most rigorous evaluation to date of schools designed explicitly for personalized learning.

Below are some observations about a few of the study’s findings, organized as a set of questions most interesting to me:

- Do students in personalized learning (PL) schools demonstrate more learning growth than students like them in traditional schools?

- Do students in PL schools outperform students like them regardless of their incoming performance?

- Given that 56 of 62 schools in the study are charters, is their superior performance actually associated with choice rather than personalized learning approaches?

- What do we know about how students in PL schools fare on indicators of student success beyond reading and math scores?

Question #1: Do students in PL schools demonstrate more learning growth than students like them in traditional schools?

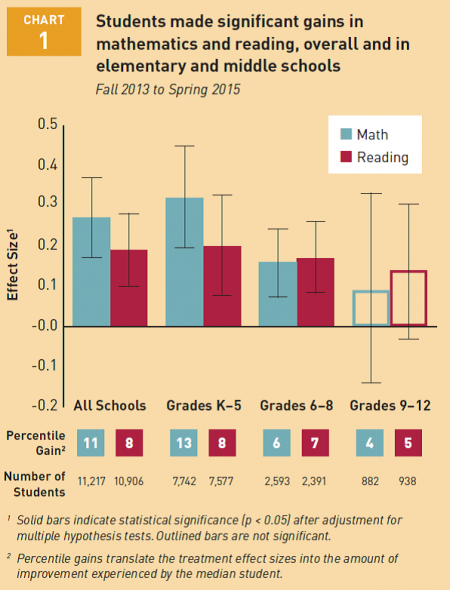

Yes. The study uses a virtual comparison group (VCG) approach, the most rigorous methodology possible for this group of schools. In all grade levels, students in PL schools did better than students like them in traditional schools. The effect sizes in elementary and middle school math and reading are positive, large and statistically significant. In high school the results are positive and moderate, but not statistically significant due to small numbers of students in some of the high schools in the sample.

As in prior years of the study, the authors struggle to convert the effect sizes into plain language. They estimate what the effect size means in terms of the median percentile gain on the MAP exam, then show the difference between this and an estimate of what the median gain would have been in a non-PL school. These differences are impressive, but the metric is still pretty abstract for most of us to really grasp the magnitude of the results. The study misses a chance for easy-to-understand comparisons to other well-known studies. CREDO and Mathematica convert effect sizes for school evaluations into “additional days of learning.” RAND does this in other studies, too. It’s a little more complicated since the PL results are based on growth rather than absolute scores. But we just need an estimate. I hope some enterprising researcher will take the PL data set and convert the effect sizes into “days of learning” so we can more easily compare the results to other improvement strategies. Anyone know an ambitious economics of education doctoral candidate who is up for the challenge?

Question #2: Do students in PL schools outperform students like them regardless of their incoming performance?

Yes. Students in every performance quintile outperformed students like them in non-PL schools. Students who started out furthest behind gained the most, which is important if they are to catch up and eventually surpass grade-level expectations.

But what about students who aren’t behind to begin with? In prior years of this study and in some other PL evaluations, fewer than half of students at the top did better than similar students in non-PL schools. But not this time – more than 60% of students in the top quintile outperformed other students like them in the VCG. This is an important finding. One of the aims of personalized learning is to meet every student where they are and help them reach their full potential. It’s possible that as the field matures from the earliest pioneers to more established approaches, the models are strengthening their ability to serve all students better.

Question #3: Given that 56 of 62 schools in the study are charters, is their performance actually associated with choice rather than personalized learning approaches?

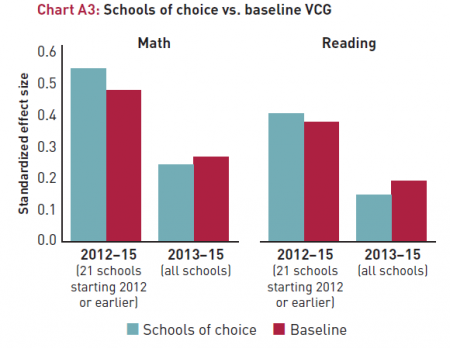

Probably Not. For each of the 11,000 students in the study, RAND researchers created a VCG of 50 students from the MAP database who are as similar as possible in starting achievement and demographic characteristics. This design allows for the kinds of comparisons I described earlier and for a variety of sensitivity analyses. To control for the fact that so many of the PL schools are charters, the RAND team created an additional VCG comprised only of students from schools of choice.

Students in PL schools out-performed the choice-only VCG in math and reading. In fact, the 3-year sample did a little better against the choice-only VCG (blue) than the baseline VCG used throughout the study (red).

These data don’t address every question about whether the charter schools in this study would be superior to the baseline VCG even if they were not designed for PL. But as the RAND team put it, they “do not cast doubt” on the main findings that students in the PL schools did better than students like them in non-PL schools, including other schools of choice.

Question #4: What do we know about how students in these PL schools fare on indicators of student success beyond reading and math scores?

Nothing. This might be the biggest limitation of the study and is a huge opportunity for future studies. Most of the teams launching new schools or redesigning existing schools for personalized learning are aiming for an expanded definition of student success. One that goes beyond helping students score better on reading and math tests. They are focused on helping students develop the agency, skills and mindsets that will help them succeed over the course of their lives. If the RAND study continues beyond year three, I hope they will incorporate these kinds of measures.

As we think about our research and evaluation agenda at NewSchools, generating useful evidence about this expanded definition of success is a top priority.